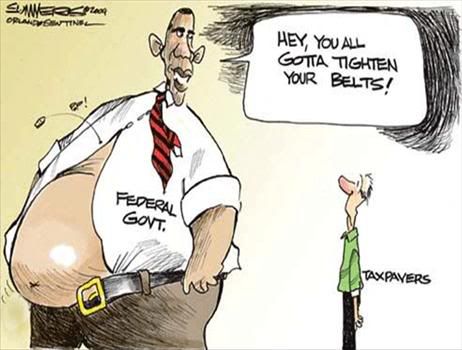

It was nearly two weeks ago that the House of Representatives, acting in a near-frenzy after the disclosure of bonuses paid to executives of AIG, passed a bill that would impose a 90 percent retroactive tax on those bonuses. Despite the overwhelming 328-93 vote, support for the measure began to collapse almost immediately. Within days, the Obama White House backed away from it, as did the Senate Democratic leadership. The bill stalled, and the populist storm that spawned it seemed to pass.

But now, in a little-noticed move, the House Financial Services Committee, led by chairman Barney Frank, has approved a measure that would, in some key ways, go beyond the most draconian features of the original AIG bill. The new legislation, the "Pay for Performance Act of 2009," would impose government controls on the pay of all employees -- not just top executives -- of companies that have received a capital investment from the U.S. government. It would, like the tax measure, be retroactive, changing the terms of compensation agreements already in place. And it would give Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner extraordinary power to determine the pay of thousands of employees of American companies.

The purpose of the legislation is to "prohibit unreasonable and excessive compensation and compensation not based on performance standards," according to the bill's language. That includes regular pay, bonuses -- everything -- paid to employees of companies in whom the government has a capital stake, including those that have received funds through the Troubled Assets Relief Program, or TARP, as well as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (emphasis mine)

And you would be judged, not on ordinary performance standards, mind you; but on government standards. You know, the kind of really really high standards by which say, Post Office employees, or IRS employees; or, the stratospherically high standards by which members of Congress are judged.

Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to the Wonderful World of Incompetence Rewarded! Because that's what government "performance standards" always lead to. When I was at NASA we used to joke about "Performance Awards"--which were given out like candy every year to just about everyone (you see, all government agencies are highly invested in being exceptionally politically correct and multiculturally sensitive). As I recall, the saying used go that the Awards were like hemorrhoids...in the end, every a$$hole gets one.

This proposal is a sick, bizarre joke, right? A joke perpetrated by the moronic, unparalleled idiot Barney Frank, Supreme Overlord of the Incompetent? Because, if something like this actually passes Congress, then I'm certain that I won't be the only one going Galt in the near future.

Do these jackasses want the economy of the U.S. to collapse? I think the spirit of Ayn Rand must be laughing and saying, "I told you so...."

From Atlas Shrugged, Part III, Chapter 6:

He knew that the reason behind the Plan was Orren Boyle; he know that the working of an intricate mechanism, operated by pull, threat, pressure, blackmail--a mechanism like an irrational adding machine run amuck and throwing up any chance sum at the whim of any moment--had happened to add up to Boyle's pressure upon these men to extort for him this last piece of plunder. He knew also that Boyle was not the cause of it or the essential to consider, that Boyle was only a chance rider, not the builder, of the infernal machine that had destroyed the world, that it was not Boyle who had made it possible, nor any of the men in this room. They, too, were only riders on a machine without a driver, they were trembling hitchhikers who knew that their vehicle was about to crash into its final abyss--and it was not love or fear of Boyle that made them cling to their course and press on toward their end, it was something else, it was some one nameless element which they knew and evaded knowing, something which was neither thought nor hope, something he identified only as a certain look in their faces, a furtive look saying: I can get away with it. Why?--he thought. Why do they think they can?

"We can't afford any theories!"cried Wesley Mouch. We've got to act!"

"Well, then, I'll offer you another solution. Why don't you take over my mills and be done with it?"

The jolt that shook them was genuine terror.

"Oh no!" gasped Mouch.

"We wouldn't think of it!" cried Holloway.

"We stand for free enterprise!" cried Dr. Ferris.

"We don't want to harm you!" cried Lawson. "We're your friends, Mr. Reardon. Can't we all work together? We're your friends."

There across the room, stood a table with a telephone, the same table, most likely, and the same instrument--and suddenly Reardon felt as if he were seeing the convulsed figure of a man bent over that telephone, a man who had then known what he, Reardon, was now beginning to learn, a man fighting to refuse him the same request when he was now refusing to the present tenants of this room--he saw the finish of that fight, a man's tortured face lifted to confront him and a desperate voice saying steadily: "Mr. Reardon, I swear to you.. by the woman I love...that I am your friend."

This was the act he had then called treason, and this was the man he had rejected in order to go on serving the men confronting him now. Who, then, had been the traitor?--he tought; he thought it almost without feeling, without right to feel, conscious of nothing but a solemnly reverent clarity. Who had chosen to give its present tenants the means to acquire this room? Whom had he sacrificed to whose profit?

"Mr. Reardon!" moaned Lawson. "What's the matter?"

"He turned his head, saw Lawson's eyes watching hm fearfully and guess what look Lawson had caught in his face.

"We don't want to seize your mills!" cried Mouch.

"We don't want to deprive you of your property!" cried Dr. ferris. "You don't understand us!"

"I'm beginning to."

A year ago, he thought, they would have shot him; two years ago, they would have confiscated his property; generations ago, men of their kind had been able to afford the luxury of murder and expropriation, the safety of pretending to themselves and their victims that material loot was their only objective. But their time was running out and his fellow victims had gone, gone sooner than any historical schedule had promised, and they, the looters, were now left to face the undisguised reality of their own goal.

"Look, boys," he said wearily. "I know what you want. You want to eat my mills and have them, too. And all I want to know is this: what makes you think it's possible?"

"I don't know what your mean, " said Mouch in an injured tone of voice. "We said we didn't want your mills."

"All right. I'll say it more precisely. You want to eat me and have me, too. How do you propose to do it?"

"I don't know how you can say that, after we've given you every assurance that we consider you of invaluable importance to the country, to the steel industry, to--"

"I believe you. That's what makes the riddle harder. You consider me of invaluable importance to the country? Hell, you consider me of invaluable importance even to your own nec ks. You sit there, trembling, because you know that time is as short as that. Yet you propose a plan to destroy me, a plan which demands, with an idiot's crudeness, without loopholes, detours or escape, that I work at a loss--that I work, with every ton I pour costing me more than I'll get for it--that I feed the last of my wealth away until we all starve together. That much irrationality is not possible to any man or any looter. For your own sake--never mind the country's or mine--you must be counting on something. What?"

He saw the getting-away-with-it look on their faces, a peculiar look that seemed secretive, yet resentful, as if, incredibly, it were he who was hiding some secret from them.

"I don't see why you should choose to take such a defeatist view of the situation," said Mouch sullenly.

"Defeatist? Do you really expect me to be able to remain in business under your Plan?"

"But it's only temporary!"

"There is no such thing as a temporary suicide."

"But it's only for the duration of the emergency!" Only untile the country recovers!"

"How do you expect it to recover?"

There was no answer.

"How do you expect me to produce after I go bankrupt?"

"You won't go bankrupt. you'll always produce," said Dr. Ferris indifferently, neither in praise nor in blame, merely in the tone of stating a fact of nature, as he would have said to another man, You'll always be a bum. "You can't help it. It's in your blood. Or, to be more scientific: you're conditioned that way."

Reardon sat up. it was as if he had been struggling to find the secret combination of a lock and felt, at those words, a faint click within, as of the first tumbler falling into place.

"It's only a matter of weathering this crisis, " said Mouch, "of giving people a reprieve, a chance to catch up."

"And then?"

"Then things will improve."

"How?"

There was no answer.

"What will improve them?"

There was no answer.

"Who will improve them?"

"Christ, Mr. Reardon, people don't just stand still!" cried Holloway. "They do things, they grow, they move forward."

"What people?"

Holloway waved his hand vaguely. "People," he said.

"What people? The people to whom you're going to feed the last of Reardon Steel, without getting anything in return? The people who'll go on consuming more than they produce?"

"Conditions will change."

"Who'll change them?"

There was no answer.

"Have you anything left to loot? If you didn't see the nature of your policy before--it's not possible that your don't see it now. Look around you. All those damned People's States all over the earth have been existing only on the handouts which you squeezed for them out of this country. But you--you have no place left to sponge on or mooch from. No country on the face of the globe. This was the greatest and last. You've drained it. You've milked it dry. Of all that irretrievable splendo, I'm only one remnant, the last. What will you do, you and your People's Globe, after you've finished me? What are you hoping for? What do you see ahead--except plain, stark, animal starvation?"

They did not answer. They did not look at him. Their faces were expressions of stubborn resentment, as if his were the plea of a liar.

Then Lawson said softly, half in reproach, half in scorn, "Well, after all, you businessmen have kept predicting disasters for years, youv've cried catastrophe at every progressive measure and told us that we'll perish--but we haven't." He started a smile, but drew back from the sudden intensity of Rearden's eyes.

Reardon had felt another click in his mind, the sharper click of the second tumbler connecting the circuits of the lock. He leaned forward. "What are you counting on?" he asked; his tone had changed, it was low, it had the steady, pressing, droning sound of a drill.

"It's only a matter of gaining time!" cried Mouch.

"There isn't any time left to gain."

"All we need is a chance!" cried Lawson.

"There are no chances left."

"It's only until we recover!" cried Holloway.

"There is no way to recover."

"Only until our policies begin to work!" cried Dr. Ferris.

"There is no way to make the irrational work." There was no answer. "What can save you now?"

"Oh, you'll do something!" cried James Taggart.

Then--even though it was only a sentence he had heard all his life--he felt a deafening crash within him, as of a steel door dropping open at the touch of the final tumbler, the one small number completing the sum and releasing the intricate lock, the answer uniting all the pieces the questions and the unsolved wounds of his life.

In the moment of silence after the crash, it seemed to him that he heard Franciscos's voice, asking him quietly in the ballroom of this building, yet asking it also here and now: "Who is the guiltiest man in this room?" He heard his own answer of the past: "I suppose--James Taggart?" and Francisco's voice saying without reproach: "No, Mr. Reardon, it's not James Taggart, "--but here, in this room and this moment, his mind answered: "I am."

He had cursed these looters for their stupid blindness? It was he who had made it possible.

You definitely need to read the entire book; and if you haven't read it in a long time, you need to read it again.

UPDATE: BTW, the answer to my rhetorical question (Do these jackasses want the economy of the U.S. to collapse?) is clearly, yes.

March 30th turned to be quite a day for our domestic auto industry. Amidst the hullabaloo over Obama’s decision to fire former General Motors CEO Richard Wagoner, few noticed the U.S. Department of Transportation's release of a new 262-page regulation requiring automakers to meet yet another costly round of fuel-economy standards for cars and light trucks. (See Department of Transportation press release here.)

[...]

The Detroit News reported that the new standard will saddle Detroit’s reeling auto industry (and their dwindling number of consumers) with considerable new costs, costs that consumers may not recoup for almost eight years...

Yes. That should just about do it for the auto industry, Detroit, and Michigan.

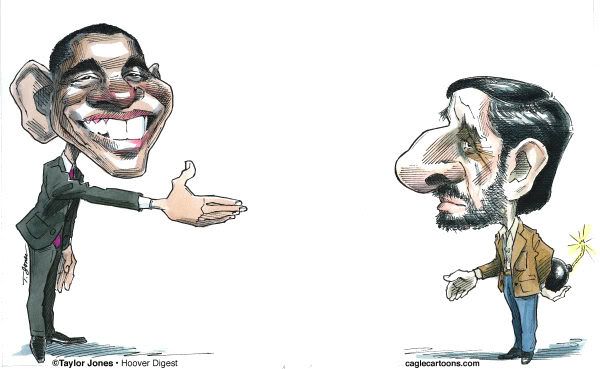

Why in the world would anyone think that the President and Vice President of the United States of America would be in a conspiracy with Islamofascists who openly state their intention of destroying both our country and our way of life? To what purpose? What could possibly be gained?

Why in the world would anyone think that the President and Vice President of the United States of America would be in a conspiracy with Islamofascists who openly state their intention of destroying both our country and our way of life? To what purpose? What could possibly be gained?